Dido Class

HMS Argonaut, the final addition to the Dido Class Light Cruisers built during the war, was completed in August 1942 at the Cammell Laird shipyard in Birkenhead. Equipped with five 5.25″ guns, the ship boasted three forward turrets and two aft turrets. Additionally, it featured six 21″ torpedo tubes and depth charges. During the war, the vessel accommodated a crew of 550 members and had two beloved mascots. Maiski the Dog joined in Murmansk in October 1942, while Minnie the Cat became a part of the crew in Hebburn-on-Tyne in December 1943.

Following the sinking of HMS Coventry, a Ceres Class Light Cruiser, by German JU-87 dive-bombers off the coast of Egypt in September 1942, the City of Coventry adopted HMS Argonaut. Throughout the war, the Councillors and Citizens of Coventry maintained a close connection with the ship, offering their unwavering support.

Under the command of Captain Longley-Cook, HMS Argonaut embarked on her inaugural mission as part of the 10th Cruiser Squadron in the Home Fleet. Departing from Rosyth in Scotland on October 13th, 1942, the ship was escorted by HMS Intrepid and HMS Obdurate as it headed towards Spitzbergen, a Norwegian island located in the Arctic Circle. The purpose of this voyage was to disembark a number of 3.7″ Naval Guns and a detachment of Norwegian Soldiers. Their objective was to establish a gunnery position to disrupt Axis shipping in the area.

After completing its operations in Spitzbergen, HMS Argonaut continued its eastward journey to Murmansk in the Kola Inlet, Russia. The ship carried essential spare parts destined for Allied bombers that had been flown there by British and Australian pilots, intended for use by the Russian forces. Unfortunately, the treacherous weather conditions during the convoy resulted in the loss of three crew members who were swept overboard.

One of the fallen crew members, Leonard Douglas Brereton, is commemorated at the Lawford Memorial in Bedfordshire. The inscription reads: “Leonard Douglas Brereton – Able Seaman P/JX157102 HMS Argonaut RN died Friday 16th October 1942, aged 21. Son of William and Lily Brereton of Lawford Beds. Commemorated Portsmouth Naval Memorial panel 03 column 2.” Meanwhile, the pilots of the bombers, along with 245 officers and men from RAF Hampden and the crews of three motor minesweepers, returned to Scapa Flow on board HMS Argonaut. Unfortunately, many of them fell victim to seasickness during the voyage.

In December 1942, HMS Argonaut became a part of Force Q. On December 1st, as a member of the 12th Cruiser Squadron, the ship, along with HMS Aurora and HMS Sirius, and supported by the Destroyers HMS Quentin and HMAS Quiberon, engaged in a fierce battle with the enemy. During the hour-long confrontation, the squadron successfully sank the Italian Destroyer Folgore and four Troopships. Additionally, they managed to damage the Destroyer da Recco and three Torpedo-boats, which were en route to North Africa to reinforce Rommel’s Campaign. However, on the return journey to base, the squadron came under heavy air attack, resulting in the sinking of HMS Quentin by German torpedo aircraft. Fortunately, the survivors were rescued by HMAS Quiberon.

On December 13th, Argonaut, along with HMS Aurora, HMS Eskimo, and HMS Quality, departed from Bone to intercept another Axis convoy. However, due to delays in setting sail, they missed their target. The following day, December 14th, 1942, at 06:00, HMS Argonaut was struck by two torpedoes from the Italian Submarine Mocenigo, causing severe damage to the ship as both her bow and stern were blown off. While dealing with the extensive damage, the vessel endured an aircraft attack, narrowly avoiding a direct hit to the starboard quarter. Tragically, three crew members lost their lives in the explosion.

Despite the critical condition of the ship, HMS Argonaut persevered under constant harassment from aircraft, using only two of its four propellers, and made its way to Gibraltar via Algiers. In Gibraltar, an improvised bow was constructed, but it proved to be ineffective. The Germans, believing that the Argonaut had been sunk, reported its demise on German Radio. In response, the National Savings Committee announced that the City of Coventry had raised £2,250,000 to fund the replacement of the lost vessel, following the Axis’ false announcement.

In December 1942, HMS Argonaut became a part of Force Q. On December 1st, as a member of the 12th Cruiser Squadron, the ship, along with HMS Aurora and HMS Sirius, and supported by the Destroyers HMS Quentin and HMAS Quiberon, engaged in a fierce battle with the enemy. During the hour-long confrontation, the squadron successfully sank the Italian Destroyer Folgore and four Troopships. Additionally, they managed to damage the Destroyer da Recco and three Torpedo-boats, which were en route to North Africa to reinforce Rommel’s Campaign. However, on the return journey to base, the squadron came under heavy air attack, resulting in the sinking of HMS Quentin by German torpedo aircraft. Fortunately, the survivors were rescued by HMAS Quiberon.

On December 13th, Argonaut, along with HMS Aurora, HMS Eskimo, and HMS Quality, departed from Bone to intercept another Axis convoy. However, due to delays in setting sail, they missed their target. The following day, December 14th, 1942, at 06:00, HMS Argonaut was struck by two torpedoes from the Italian Submarine Mocenigo, causing severe damage to the ship as both her bow and stern were blown off. While dealing with the extensive damage, the vessel endured an aircraft attack, narrowly avoiding a direct hit to the starboard quarter. Tragically, three crew members lost their lives in the explosion.

Despite the critical condition of the ship, HMS Argonaut persevered under constant harassment from aircraft, using only two of its four propellers, and made its way to Gibraltar via Algiers. In Gibraltar, an improvised bow was constructed, but it proved to be ineffective. The Germans, believing that the Argonaut had been sunk, reported its demise on German Radio. In response, the National Savings Committee announced that the City of Coventry had raised £2,250,000 to fund the replacement of the lost vessel, following the Axis’ false announcement.

To undergo repairs, HMS Argonaut had to make a treacherous journey across the U-boat-infested Atlantic. On April 4th, 1943, under the command of Captain Haynes RN, the ship departed from Gibraltar accompanied by its escort, HMS Hero. After a few days, on April 7th, they arrived in Ponta Delgada, located on the Portuguese islands of the Azores. According to the World Government Convention, ships engaged in war were permitted to seek shelter in neutral ports for a maximum of three days to carry out urgent repairs. However, upon arrival, the crew of HMS Argonaut was surprised to find a German U-boat undergoing repairs alongside them.

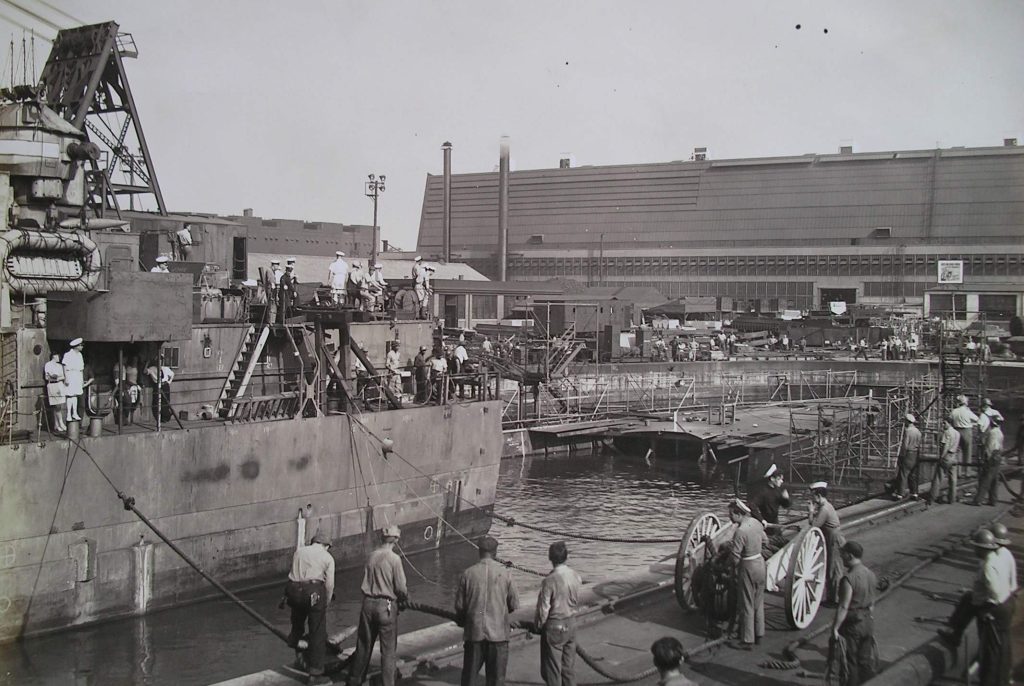

On April 8th, just a few hours after the German U-boat, HMS Argonaut set sail. Despite anticipating a potential attack from the U-boat, none occurred. However, HMS Hero encountered engine problems and was detached by the Admiralty on April 9th, leaving HMS Argonaut to continue its journey across the Atlantic alone. On April 13th, USS Butler was spotted and joined the Argonaut on its voyage. After additional hull repairs in Bermuda, the ships reached their destination on April 17th. Subsequently, on April 27th, under the escort of USS Tumult and USS Pioneer, HMS Argonaut set sail once again, finally arriving at the port of Philadelphia on April 30th, 1943, where repairs would take place.

“CRUISER WRECK GOT HOME” (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) IT IS DISCLOSED TODAY THAT THE BRITISH CRUISER, ARGONAUT, NOW IN THE PACIFIC, WAS ONE-THIRD REBUILT IN THE PHILADELPHIA NAVY YARD AFTER THE GERMANS THOUGHT THEY HAD SUNK HER IN THE MEDITERRANEAN IN THE SPRING OF 1943.

THE COURAGE OF THE CREW ENABLED HER TO CROSS THE ATLANTIC AFTER SHE HAD RECEIVED A BARRAGE OF TORPEDOES, AND SKILLED WORKERS REPLACED HER BOW AND STERN. THE GERMANS HAD EVERY REASON TO BELIEVE THEY SPOKE THE TRUTH WHEN THEY PROCLAIMED THEY HAD SUNK THE ARGONAUT, SAID THE NAVY DEPARTMENT, FOR A SPREAD OF FISH FIRED BY A SUBMARINE JUST BEFORE DAWN, BLEW OFF HER BOW AND BLASTED AWAY HER ENTIRE STERN, INCLUDING HER RUDDER AND TWO OF HER PROPELLERS. BY DOGGED DETERMINATION, THE ROYAL NAVY BROUGHT THE CRIPPLE ACROSS THE ATLANTIC UNDER HER OWN POWER. THE CREW STEERED HER WITH TWO REMAINING PROPELLERS BY SPEEDING ONE AND SLOWING THE OTHER. HER SPEED ONCE DROPPED AS LOW AS 4 KNOTS, BUT SHE CAME THROUGH.

FULLY IMPRESSIVE FROM THE OFFICIAL POINT OF VIEW WAS THE WAY THE NAVY YARD, CRAMMED WITH BATTLE-DAMAGED JOBS AND NEW CONSTRUCTION, TACKLED THE FRESH PROBLEM OF RE-BUILDING A FOREIGN SHIP. IN SPITE OF THE DIN CAUSED BY ALL THE WELDING AND RIVETING THAT HAD TO BE DONE, THE CREW LIVED ABOARD WHILE THE REPAIRS WERE BEING MADE. ACCORDING TO THEIR ALLIES, THEIR ONLY REQUEST WAS “HURRY IT UP IF YOU CAN. WE WANT TO GET BACK OUT THERE.”

The repairs in Philadelphia completed on November 13th, 1943. On returning to Britain on December 2nd, 1943 Captain Longley-Cook re-joined and Argonaut joined the Home Fleet once again.

On June 4th, 1944, HMS Argonaut, alongside HMS Belfast, HMS Diadem, HMS Orion, HMS Ajax, and HMS Emerald, departed from Greenock as part of the 10th Cruiser Squadron. Their mission was to join Operation Neptune, the naval component of the Normandy invasion (D-Day), with Force K stationed off Gold Beach. To the surprise of the crew, Captain Longley Cook announced that if the ship was hit, he would attempt to ground her and continue firing. On the first day alone, the ship fired 400 shells and was struck by an enemy projectile that penetrated the quarterdeck but emerged on the starboard side without causing any injuries. Overall, HMS Argonaut fired a total of 4,359 shells in support of the land forces.

The ship received congratulations from General Miles Dempsey, the officer in charge of the British Second Army, for its exceptional gunnery accuracy, especially during the intense battles for Caen, which lay approximately 12 miles inland—the outer limit of the ship’s range. During the campaign, Argonaut had to make a quick return to Portsmouth for replenishing ammunition.

In August, HMS Argonaut was transferred to the Mediterranean for Operation Dragoon, operating under the command of the US Eighth Fleet. Second only to the Normandy invasion, Operation Dragoon was the controversial Allied invasion of the French Mediterranean coast, which faced challenges and disagreements within the American and British hierarchy. The British aimed to push into the Balkans and outpace the Soviets, while President Roosevelt, seeking reelection, saw the Balkans as a British postwar interest. Meanwhile, the cunning Soviet dictator, Joseph Stalin, covertly eyed the region for himself while backing the US stance. Ultimately, Operation Dragoon proved to be a resounding success. It achieved its military objectives, decimated Hitler’s 19th Army, captured over 100,000 German prisoners, liberated the southern two-thirds of France, and linked up with the Normandy invasion forces, all within 30 days. However, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, until his dying day, believed that Operation Dragoon was a strategic error that paved the way for Soviet domination over much of Eastern Europe.

In January 1945 she was ordered to join the British Pacific fleet in Sydney Australia. The British Pacific fleet was the largest ever fleet ever assembled it consisted of a total of 336 ships and 300 aircraft. Captain Longley-Cook left the ship upon his promotion to Vice-Admiral the new Commanding Officer was Captain W.P. McCarthy RN.

In February 1945 Argonaut sailed for Manus the forward operating base for the British and American fleets Argonaut took part in the shelling of positions at Saskishima while the Americans concentrated on Okinawa. She was withdrawn in August 1945 and sailed to Formosa (now Taiwan) to help with the evacuation of British Prisoners of War from the port of Kiirun on September 5, 1945. Then the Argonaut sailed for Shanghai to repatriate British internees. Hong Kong was the ship’s next stop for a similar mission.

After completing her service, HMS Argonaut returned to Portsmouth, Britain, on July 6th, 1946. She was then decommissioned and placed in reserve, without being re-commissioned again. In November 1955, she arrived at Cashmore’s Shipyard in Newport, Gwent, South Wales, for disposal.